Interview The Wrath of God for Diário de Notícias

- Four years after The Captain’s Daughter you return to the same literary genre. Why is that?

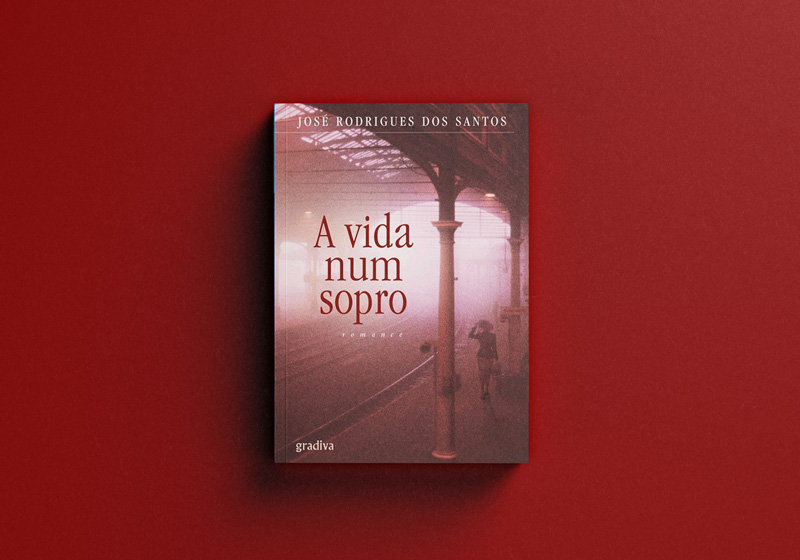

JRS. Because I do not want to become a predictable author and because it’s crucial to surprise readers. It’s important to master different genres, so I need some literary versatility. Life in a Breath is a love story, but also an historic novel, a portrait of an age, a philosophical essay, in fact a little bit like The Captain’s Daughter. If you look closely, however, you’ll see that this novel is not very different when compared to my other books. Through Life in a Breath, I try to make readers understand the rise and popularity of Salazar’s dictatorship in the 1930s. And, in fact, that’s what I do in all my novels: I use fiction to explain reality.

- Professor Noronha’s saga has reached its end or is this new novel of yours a simple break from the thriller genre?

JRS. After a trilogy with Tomás, I thought it was high time to leave him alone for a while. But I’m not through with him. He’s going to return.

- Mystery thrillers were the genre that brought the Portuguese public to you. Why swap them for a different kind of fiction?

JRS. I thought it was the right moment to make a break from the sequence of historical and scientific thrillers. I felt the need to surprise readers and give them something different, though still based on the same essential idea: to make sure my novels are not pastime, but gaintime. You know, History is always written by the winners and the simple truth is that losers have a different version of it, albeit silenced. The Salazar dictatorship was defeated by the 1974 democratic revolution and, in contemporary discourse, the dictatorship become a devil of sorts in the Portuguese 20th century. But the undeniable fact, though conveniently hidden, is that Salazar was a very popular man in the 1930s. Many Portuguese people thought he was some kind of Messiah, a perception that only changed from 1945 onwards, with the Allied victory in the Second World War. And this is the crucial point: if Salazar was such a bad person, why did a lot of people in the country love him? What did he bring to Portugal? It was to answer these questions that I wrote Life in a Breath and I hope this novel will help us understand Salazar’s rise to power.

- So, you want to stay in this genre’s tracks…

JRS. It’s possible. Look, I try to get versatility in my writing and I try to surprise readers. That’s why I do not exclude a single genre.

- Are you going to write a sequel to Life in a Breath?

JRS. Gosh, it’s too early to say.

- And The Seventh Seal? Are you going to continue it?

JRS. It’s not in my plans. The Seventh Seal is a novel about global warming and the end of oil. I don’t think there is much sense in coming back to the same subjects. When Tomás Noronha comes back, it’s going to be with a completely different story and subject.

- What genre do you feel more at ease? This one or the thriller?

JRS. I feel perfectly at ease with any genre. What really matters is that I enjoy writing a book and the reader enjoys reading it.

- What kind of research did you undertake for this novel?

JRS. Mainly historical research. I looked into History books, documental archives and the newspapers published in the 1930s. And I spoke with people from my family, because the novel includes the story of my family. In fact, the fictional starting points for this novel were the following questions: what would have happened if my father’s parents met my mother’s parents? What if my mother’s mother had married my father’s father? You can see there’s a lot to explore here…

- How long did the novel take to write?

JRS. I began writing it in 2005 and published it in 2008, so it’s three years of working. But it wasn’t continuous work. In this period I wrote two other novels too, The Einstein Enigma and The Seventh Seal. Let us say that Life in a Breath kept maturing throughout all this time.

- Where did you write it?

JRS. At home, as usual.

- Your books are usually bestsellers in Portugal. Do you think Life in a Breath will follow the same path?

JRS. I believe readers are going to enjoy this novel, yes. It has love and war, history, philosophy, action. And it talks about us.

- If we had to find similarities, we could say that Codex 632, The Einstein Enigma and The Seventh Seal were in the Dan Brown line. What about this one?

JRS. It’s the José Rodrigues dos Santos line, I guess.

- Have you got a bit of Camilo Castelo Branco’s influence?

JRS. No, not at all. You see, my novels are mine, I do not know of any author who writes novels the way I write them. This writing style is part of my identity, a sort of literary finger print. But of course I’m influenced by other authors. Perhaps in this novel you can find a little bit of Somerset Maugham, a little bit of Isabel Allende, a little bit of Jeffrey Archer, a little bit of Eça de Queiroz. But that’s not conscious.

- You already sold more than half a million books. What do you feel about it?

JRS. If, a few years ago, someone told me this would happen, I would laugh in his face. But it did happen.

- How do you explain that readers remain so faithful to you and enjoy so much your writing?

JRS. You’ve got to ask them, of course. But I think there are three main reasons: the story, the writing style and the fiction-non fiction mix. As you know, I do invest a lot in the story, my novels have some action, there’s always something going on, the plot advances and there are twists, surprises and suspense. All that is important. On the other hand my writing is not complicated, something that turns many readers off from Portuguese novels. I recall having received, a few years ago, an e-mail from a reader who said the following: “Everybody on television and newspapers say we have great authors and great books and I reach the conclusion that the dumb ones are us, the readers, because once we arrive at the beach we see everybody reading Spanish, British, American or French authors and nobody cares about Portuguese authors. We supposedly have great writers, but nobody can read them, they are unreadable. But because no one can blame them, since they are so good that whoever criticizes them is immediately humiliated, it seems that the culprits are exclusively us, the readers, the stupid ones, the uncultured ones.” I think this e-mail sums up the general feeling among many readers who feel unattracted to Portuguese authors. A lot of writers in Portugal enjoy experimental writing, but most readers hate it. I think I played for these readers. You see, I always try to make my writing transparent, I believe that words are at the service of the story and not the other way round, and I think readers enjoy that. Finally, the non fictional side to my fiction seems to carry some weight too. Through a fictional story, I try to convey non fictional information. It’s again that idea of novels as gaintime, not pastime. Let’s call it faction, a mix between fact and fiction. I believe faction plays an important part in the success of these novels. The reader reads a story that entertains him, but he also learns something about the world where he lives in.

- What do you think about the fact that well-established writers, such as Lobo Antunes and Novel laureate José Saramago, end up behind you in the bestselling charts?

JRS. I’m not aware of José Saramago’s and Lobo Antunes’ sales, so it’s a bit difficult to answer that one. But, at least in Saramago’s case, I’m not sure my novels sell better. Fact is, I do not know their figures…

- Do you think Life in a Breath’s story could have taken place in the real world?

JRS. Sure. In fact, the story was not just made up. What is narrated in Life in a Breath did take place, though to different people. You do not have to make up things when reality is so rich.

- Do you believe that impossible love stories are the ones which sell better?

JRS. I don’t know, I never thought about that. But they are interesting stories, that’s for sure.

- How does Fernando Pessoa show up in your book?

JRS. Fernando Pessoa died in the middle of the 1930s. He wasn’t an unknown author at the time, but he wasn’t as known as he is today. Let us say that he was known in intellectual circles. I thought it would be interesting to have my characters fleetingly cross their paths with him, because some of his poems reflect the spirit of his time. And, after all, Life in a Breath is a novel that tries to capture that spirit.

- You provide an e-mail address in your novels. Do you get a lot of messages from your readers?

JRS. A lot, yes. I get daily five to ten e-mails and I answer them all.

- What kind of e-mails?

JRS. All kinds and from everywhere. Most are from Portugal, of course, but I do get a lot of e-mails from Brazil, Italy, the United States, Mozambique, Holland, Argentina, Switzerland… everywhere. It’s quite interesting to be able to talk to your readers. That’s an experience I strongly recommend to other writers.

- Do you think Portuguese authors write in a way that is able to seduce international readers?

JRS. It depends on the readers and on the authors. But, as a general rule, I would say no, unless we are talking about niches. International readers look at a Portuguese author the same way they would look at a Bulgarian or Bolivian author. With the exception of José Saramago and perhaps Fernando Pessoa, we do not have authors that are able to be regarded in international bookstores as mainstream.

- Your writing rate is different when compared to most Portuguese writers – this time we are talking about 612 pages. How do you manage to write so quickly?

JRS. Perhaps because I write as a professional since I was 17 years old, when I began my career as a journalist. Every day I produce a lot of written pages. Doing that as an author was just a small step.

- Do you never get writer’s block?

JRS. Never. I do not know what writer’s block is. I do not doubt that it exists, but I’ve never been through that experience. I build the book in my head, sometimes even a sequence or a dialogue, and the difficulty lies in the inability of my fingers to be quick enough to register the ideas that flow from my mind. It’s as if from my head there was a haemorrhagic stream of narrative, sometimes it’s so much that I cannot stop it.

- How do you like to write? In the morning, in the evening, after a coffee…

JRS. In mornings and afternoons. When it’s eight o’clock in the evening, I stop. If I don’t, it will be difficult to relax my mind and fall asleep.

- Do you rather prefer books that require research or books that require inspiration, like this one?

JRS. Do you think this novel is all inspiration? It’s not! Life in a Breath took a lot of research, have no doubt about it. Perhaps the research is hidden, but it’s there. Actually, all my novels require a lot of research. As the saying goes, it’s 5 per cent inspiration and 95 per cent perspiration.